Albert Shanker: Prophetic reformer

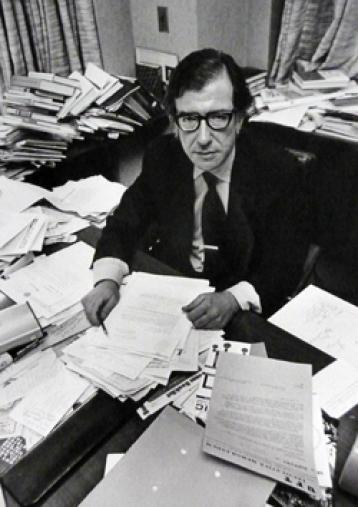

Al Shanker at his UFT office.

by Susan Amlung

If a controversial topic is dominating the education debate today, it’s probably something that Al Shanker proposed decades ago.

Count among the ideas he espoused such hot-button items as charter schools, national tests, differentiated teacher pay, stricter student discipline, more rigorous teacher evaluations, accountability through student testing, flexible contracts, cooperative learning, peer review, early childhood education, a core curriculum and higher academic standards.

It’s a tribute to Shanker’s forward thinking that many of the education reforms that he advocated in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s remain as cutting edge — and as contentious — today as they were when he first aired them.

The list of these ideas is long and diverse, perhaps because his philosophy could not be easily pigeonholed. Depending on the era and the issue, he was variously called liberal and conservative, hawk and dove, intellectual and thug, democrat and despot. In addition, he dominated the education scene for more than three decades, as president of the UFT (1964-1986) and then the AFT (from 1974 until his death in 1997), and wrote and spoke prolifically during that time, including 1,300 influential weekly columns in The Sunday New York Times.

But before he was an education reformer, he was a labor leader. It was the labor movement, he believed, that would complete the work of teachers to raise poor and immigrant children into the middle class and build a democratic society. It was labor that would obliterate racial tensions and class warfare, defeat totalitarianism and spread social justice in the world.

When, in the early days, teachers worried that being a unionist was “unprofessional,” he argued that it was the union that freed teachers from subservience to supervisors and enabled them to be real professionals. And even when one of his lifelong dreams — the merger of the NEA and AFT into a huge, united teaching force — hung in the balance, he was willing to risk its loss if the NEA continued to refuse affiliation with the AFL-CIO.

As the second UFT president, Shanker increased union membership from about half of New York’s teachers to 97 percent in three short years, eventually making it the largest local union in the country. And from the beginning, he preached the unorthodox view that teachers needed public support, but wouldn’t get it until they provided “leadership in the community on issues that go beyond narrow self-interest.” Thus, he led unionized teachers to deep involvement in civil rights battles in the South and in the struggle against Communism in Eastern Europe, as well as in supporting the war in Vietnam, the frequent subject of heated internal UFT dissension.

But during the infamous confrontation in Ocean Hill-Brownsville over community control and the prolonged teacher strikes of 1968, his desire for public support took a back seat to what he saw as more important issues. Foremost among them was the need to protect members’ due process rights amid the racial tensions after the local board attempted to involuntarily transfer 19 educators from the district. Beyond that, he was worried about the direction that the civil rights struggle was taking as affirmative action and Black Power began to push aside earlier goals of integration and colorblind treatment after the murder of his ally, the Rev. Martin Luther King.

Although he was widely seen as unyielding and pugilistic throughout that period, privately he was deeply upset at being called a racist. Two years later, he seized an opportunity for redress with the community when the mostly black and Hispanic paraprofessionals expressed interest in joining the UFT. That meant so much to him that he threatened to resign if teachers spurned their membership, the only time he used that threat as leverage. In later years he often said that organizing the paras was his proudest accomplishment.

In the 1980s, spurred by the publication of a highly charged Reagan administration report, A Nation at Risk, Shanker’s focus shifted to education reform, and that’s where he left his greatest legacy. Unlike many other education leaders, he supported the premise of the report — that the public schools were failing their responsibility to America and its children — and he urged the union to embrace a nationwide campaign to upgrade education. In that way, he argued, teachers would have a voice in the changes to come, public schools would benefit from the attention and ensuing investment, and teacher unions would be seen as part of the solution instead of part of the problem.

On these points, he was at least half right. Public education did enjoy a period of national prominence and increased funding, and teachers did have a place at the table — though their views were not always heeded. But now, more than a quarter century later, teacher unions still get the rap for the failings of public schools. And over the years, many of the reforms Shanker advanced became perverted by anti-union animus, mismanaged implementation and political opportunism.

Al Shanker signs the first UFT/BOE contract for paraprofessionals in 1970.

So, Shanker’s ideal of teacher-led schools granted charters to incubate innovation and provide models for wider reform became, in many instances, vehicles for other agendas. As for-profit management organizations sought to use them as cash cows and some religious and ethnic groups tried to get public funding for inculcating their views, Shanker saw his vision turn into everything he had spent his life fighting against.

And there are some today who say that had he lived to see his crusades for higher standards and accountability for teachers and students deteriorate into the current obsession for testing and test prep, he would be sorely disappointed.

Still, there is no question that without Al Shanker, public education may never have benefited from the research and reflection that his ideas spawned, and teachers might never have gained the voice and respect they command today.

Also see: A Brief Chronology of the Life of Albert Shanker and Al Shanker's Bio

Originally published in New York Teacher, February 4th, 2010