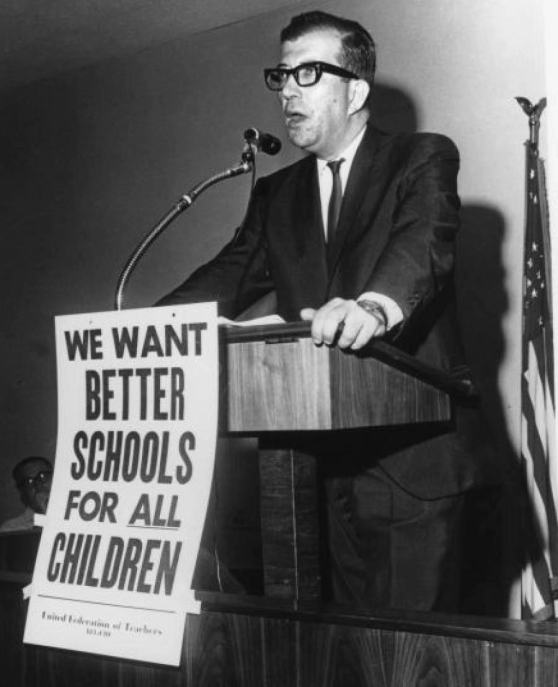

Albert Shanker

As his fledgling union teetered on the brink of a strike, Albert Shanker was the linchpin of a last-minute settlement that laid out the goals that would dominate his thinking for the rest of his life. That 1963 contract committed the UFT and the New York City Board of Education to work together to recruit well-qualified teachers, improve difficult schools, reduce class size and develop a more effective curriculum. Although his thoughts about how to achieve those goals would evolve over the years, the focus remained the same: education for children.

When Shanker, president of the 907,000-member American Federation of Teachers, died Feb. 22 at the age of 68, he left behind a legacy of school reform and belief in the dignity of public school educators that was developed and honed in the classrooms of New York City.

Shanker, UFT president from 1964 to 1986, was an articulate and fearless labor leader who was twice jailed for violating the state law that barred strikes by public employees. The first time was during the 1967 strike over smaller classes and more money for education. The second came after the 1968 Ocean Hill-Brownsville strike, which centered on a local school board's attempt to dismiss teachers without due process.

As the power of New York City's teachers union increased under his stewardship, so did Shanker's influence in other crucial arenas. During the city's fiscal crisis in 1975, which triggered a five-day strike over large class sizes, he was widely credited with helping save New York from bankruptcy. He agreed to ask the Teachers' Retirement System to bail out the city by buying $150 million of untested Municipal Assistance Corporation bonds — an investment that turned out to provide a tidy profit for the TRS.

Although his early reputation as a union militant stuck with him (a famous line in Woody Allen's 1973 film, Sleeper, blames the destruction of civilization on Shanker's getting hold of a nuclear warhead), Shanker's vision of the role of teacher unions never stopped evolving.

He never hesitated to speak his mind about what was wrong with schools — whether the audience was lawmakers, scholars, corporate heads or members of his own union — as uncomfortable as that might have made any of them.

Sometimes his blunt and often caustic appraisals drew the ire of his own members, who felt Shanker was giving aid and comfort to the enemies of public education. But Shanker steadfastly refused to play the role of cheerleader to a system that wasn't working.

While continuing his struggle to improve the lives of educators through nuts-and-bolts trade unionism, Shanker also spearheaded the drive to upgrade education nationally. He came to see teachers and their unions as vital pistons in a mighty engine that could help students succeed in the classroom and in their lives.

His course along that road took many twists and turns, including a 1980s' focus on restructuring schools and a 1990s' drive to set high national standards for student achievement that could match the records of other nations.

Shanker became an advisor to U.S. presidents from Jimmy Carter on. Indeed, Bill Clinton's 1997 State of the Union address bears a striking resemblance to the AFT's "Lessons for Life" campaign, which champions a get-tough approach to student discipline and academic standards. Minutes after delivering the address before a joint session of Congress on Feb. 4, Clinton personally called Shanker in his hospital bed to thank him for his steadfast insistence that national standards are the best way to improve public education.

In April 1983, a commission appointed by Ronald Reagan unveiled a report called "A Nation at Risk," which painted a devastating portrait of American education. Educators — who increasingly were poorly prepared for their jobs and the subjects they were teaching — had lost sight of their academic mission. Students were taking frills like courses in bachelor living rather than focusing on math, science and other staples. As a result, the United States was dead last in seven international comparisons, with test scores lower than when Sputnik had been launched 25 years before. The report recommended tougher graduation requirements, lengthening the school day and a salary schedule that smacked of merit pay.

The National Education Association immediately assailed "A Nation at Risk" as a political document. Shanker was the only major figure in education to endorse the report. He saw a great deal of truth — and a new direction for his union. He would have to spend a great deal of time persuading the education establishment — and members of his own organization — that the critics were right.

Many said Shanker's decision to embrace "A Nation at Risk" was a watershed moment, because conventional wisdom held that the only cure for education's ills was more money. Anything else was considered fire from the enemy. But Shanker saw that the report wasn't boosting vouchers or privatization. Rather, it spoke of preserving and improving public education, of raising standards and implementing accountability for both students and educators — even as he never stopped reminding politicians that teachers continued to need the resources to do the job.

He dealt with the ramifications of the report and other issues in his column, which he launched in 1970 as a weekly paid advertisement in the Sunday New York Times. In what seemed like nonstop speaking engagements across the country and even around the world, Shanker arguably became the nation's best-known advocate for improving education.

He aimed his sharpest barbs at an educational establishment that stuck ill-prepared teachers in classrooms. If higher standards were needed for students, they also were needed for teachers, he argued — and that led him to assail college education programs. At a National Press Club forum in 1985, he proposed creating the National Board of Professional Teaching Standards, a voluntary national certification body for teachers akin to board certification for physicians. The Carnegie Foundation established and funded that board in 1987 to begin research and development on just how to certify teachers; it started the actual certification process in 1994. Just last year, six UFTers passed the difficult hurdles to win board certification, bringing to 595 the total certified nationally in six of the eventual 30 subject areas.

Shanker believed that teachers across the nation have common problems and common goals — and would always be more effective working together. In 1972 Shanker and Buffalo teacher Tom Hobart brought about the merger between the New York State AFT affiliate and the rival NEA state affiliate. The new union — New York State United Teachers — is now the largest statewide union in the country. Shanker served as NYSUT's executive vice president from 1973 to 1978. Today, 25 years after its inception, that merged union, the New York State United Teachers (NYSUT), is the most influential education organization in the state — the premier voice for teachers statewide.

"I remember Al in those days. He was magnificent," recalled NYSUT President Tom Hobart. "Many people were dead set against merger. But Al took it upon himself to travel the state, meeting with teachers from both organizations, and convincing them that it would be in the best interests of teachers to be in one organization, working in unison rather than fighting each other."

Hobart added that after the merger, newspaper editorial boards warned that teachers were now too powerful. "I don't know how powerful we actually were, but there sure was a perception we were," he said, illustrating with this story: New York's new governor, Malcolm Wilson, had not been a friend to public employees. But when Wilson addressed the NYSUT convention in 1973, he surprised everyone by throwing his weight behind reducing the probationary period for teachers from five to three years, and for a dramatic 15 percent increase in state aid to education.

Once at the AFT, Shanker led the merger talks between that organization and the larger NEA in an effort to create a more powerful national voice for teachers and for children. Although initial attempts failed in the early 1970s, a few years ago he helped revive the goal of forming a single national union that would wield more clout than the two unions could separately; considerable progress had been made at the time of his death.

As an education ambassador at large, Shanker traveled the nation and, indeed, the world. But he was as passionately committed to democracy as he was to education and he also took an important leadership role in that international arena.

He headed the AFL-CIO's International Affairs Committee for many years and helped dissidents in Eastern Europe, many of whom were teachers, to bring down communism. The AFT strongly supported Lech Walesa's Solidarity Movement and the Charter 77 group in Czechoslovakia. The AFT sent its best organizers to Chile to work with teacher organizations opposing the repressive Pinochet regime, building pressure for free elections and the restoration of democracy. In South Africa, the AFT strongly supported anti-apartheid democrats and trade unionists. He also brought the full power of the AFT to bear on the countries and companies that exploit child labor.

In 1993 Shanker became the founding president of Education International, the worldwide teacher union federation formed by merger of the International Federation of Free Teachers' Unions (IFFTU), to which the AFT belonged, and the World Confederation of Organizations of the Teaching Profession, to which the NEA belonged.

Born to Russian immigrant working-class parents on Sept. 14, 1928, Al Shanker — who would develop into a stirring orator — spoke not a word of English when he entered first grade. One of the country's best-read and intellectual labor leaders, he was an average student, shying away from competition out of fear of not measuring up to his younger sister, a star student. Shanker was a gawky beanpole of a kid, reduced to hiding in his apartment to escape the anti-Semitic taunts and beatings from neighborhood toughs.

He grew up in Long Island City where Shanker's mother, Mamie, was a garment worker holding union cards in both the International Ladies Garment Workers Union and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union while his father, Morris, delivered newspapers. Both were staunch Roosevelt Democrats and ardent trade unionists; in the Shanker household "unions were just below God."

From his mother, the young boy inherited a yen and talent for spirited argument, a skill he would put to good use as head of the Stuyvesant HS debating team. Enrolling at the University of Illinois at Champagne-Urbana in 1946 — a time when university housing carried ads stating "Whites and Christians Only" — his mind ranged free. Much to the consternation of his Orthodox Jewish parents, he explored other faiths. And he blossomed politically.

Chair of the campus democratic socialist study group, Shanker brought in speakers, many of whom spoke fervently of their anti-communism. He joined an interracial group that organized sit-ins and demonstrations to protest and end segregation and discrimination; later, as a labor leader, he would stand beside Martin Luther King Jr. and march to Selma, Ala., to demand civil rights for the nation's African-American citizens.

In the late 1960s, he worked to organize thousands of classroom paraprofessionals, many of them minority group members, and began a "career ladder program," through which they could get a college education and one day become teachers. The UFT estimates that over the years more than 8,000 paras have used the program to become teachers and that many more have gotten associate's and bachelor's degrees while remaining paraprofessionals. Today, the UFT's career ladder program is the largest source of minority teachers in New York City.

Upon his own college graduation, Shanker pursued a doctorate in philosophy at Columbia University. After sailing through his coursework, Shanker had second thoughts about the practical worth of a degree in philosophy. Not intending to make it a career, Shanker tried his hand at public school teaching. The year was 1952 and his first assignment was as a substitute at PS 179 in East Harlem. "It was a lousy job," he said.

Especially irksome was the almost absolute power of the principal — and the next year Shanker and a few other teachers banded together at JHS 126 in Queens to do something about it. They organized the school for the UFT's predecessor, the Teacher's Guild.

It was an uphill fight there and at other schools that he would visit in the coming years. He and his hot-blooded JHS 126 colleagues, George Altomare and Dan Sanders, had to overcome apathy and the deep-seated belief of many teachers that unions were for blue-collar workers. The three began holding organizing mixers at Shanker's nearby apartment — with Shanker playing the role of mixologist. The lure worked. "Sure we wanted people to join for the right reasons," Altomare remembered. "But we wouldn't refuse them if they felt left out of the whiskey sour parties."

In 1959, at age 31, Shanker quit as a Manhattan junior high school math teacher to become a full-time organizer for the Guild, which in March 1960 merged with a high school teacher organization to form the UFT. He visited hundreds of schools, often using a new retirement law as the opening he needed to get in. The law had reduced the years for a pension from 35 to 30 causing confusion. "No one could understand the literature, so I studied the pension system and developed a 30-minute talk. I became a hot item on the circuit. I became a pension maven," he said.

But far too few were heeding the call to unionize, and Guild leaders saw that there was only one resolution to the internal union debate over whether to grow before acting or acting in order to grow. Shanker recalled a chance meeting with then-Mayor Robert Wagner that convinced him that teachers would have to take matters into their own hands.

"I asked Wagner why it was that during a previous negotiation he had said that there was not a penny more yet, when a hurricane came, [he] found millions of dollars. He said that was a disaster. I said, 'In other words, if we become a disaster you would find more for us, too.' We both laughed. But from that day we decided to become a disaster."

On Nov. 7, 1960, some 5,600 members hit the bricks in direct violation of a law that could have led to their immediate dismissal. Their goal was to demand collective-bargaining rights. They won and the UFT began to grow. The union struck again in 1962 to win its first contract. Shanker, then the union's secretary, was in the thick of things. In 1964 he succeeded Charles Cogen to become the UFT's second president.

Shanker is survived by his wife of 35 years, the former Edith (Eadie) Gerber, their children, Michael of Tarrytown, Jennie of Philadelphia and Adam of Mt. Vernon; a son, Carl of Gaithersburg, Md, by his first marriage; two grandchildren; and a sister, Pearl Harris, of Cleveland.