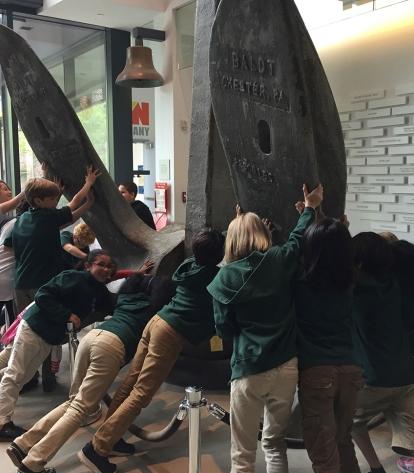

As Yokasta Evans-Lora’s class from the Brooklyn Arbor School in nearby Williamsburg arrives on June 13, teacher and students are met by high-energy museum educator Rebecca Saltzman. “How many pounds does this anchor weigh?” she asks the 3rd-graders, who can’t resist touching it and attempting to push it.

Guesses come fast and furious. “One hundred million pounds!” says one student. “Hint: it’s written on it,” Saltzman says. The correct answer is 22,500 pounds.

“How did they get the anchor inside the building?” asks a student. “Which do you think came first,” Saltzman counter-queries — the building or the anchor? The students determined the building had been built around it.

So began a class trip to the “Ingenious Innovations” exhibit, created by the Brooklyn Historical Society, which explores how ship technology has evolved over time, from early wooden ships to iron and steel steamships, aircraft carriers and more.

To the sound of waves slapping the sides of a ship, students reach into a wooden cabinet for items used on ships in the early 1800s, the days of wood and sail. “These are artifacts from a time before iPhones and Google,” Saltzman says. “What do you think they are?”

Passing them around, students make observations and guesses:

“It’s sticky and it smells,” they say of what turns out to be a very durable, and old, cloth sail.“It’s a rope. This could be useful to pull down a sail,” a student says about another artifact.

“What is this, what would you use it for?” Saltzman asks.

“It’s hairy, fuzzy,” says a student. “It’s greasy, because my fingers are greasy now,” observes another.

“That’s oakum,” Saltzman says, naming a mixture of rope and tar used to patch holes in the bottom of a ship.

“It keeps the water out of a boat, the same way as oil and water don’t mix in the lava lamps we made in our makerspace,” said Evans-Lora, referring to their classroom do-it-yourself space, where students work on inventions. “Because we’re makers, we like to tinker, think about innovation and how it changes the environment,” she added.

The Navy Yard has been a hotbed of innovation since its early days. Engineers there invented O-boats, torpedo ships, an early submarine and powerful battleships. Undersea telegraph cables first were tested there, and the first wireless radio broadcast was picked up there. The use of anesthesia was perfected at the Navy Yard by young Navy surgeon E.R. Squibb.

“Look up!” Saltzman says “Do you see anything energy efficient?”

“I see a solar panel,” says one student. “I see a street lamp,” says another.

“That’s one of the Yard’s new companies; they make solar-powered street lamps,” Saltzman explains.

After the Yard was decommissioned, it fell into disrepair and was closed to the public for decades before opening recently to innovative — and sometimes quirky — local enterprises that have created jobs and helped to revitalize the waterfront.

Students sat on a Civil War-era cannon and looked up at a gigantic photo of a ship in a dry dock, asking how the ships got inside. “Think of it as a bathtub: The boat swims into the dry dock, then they push all the water out,” said Saltzman.

At an interactive map of the Naval Yard, students put their hands over an area to see how it looked in different eras, from the 1600s to today. Before their eyes, the area went from green space to streets, from an agricultural town to an industrial city. “We’re looking at things that have changed and been repurposed, and how New York itself has changed and been repurposed,” said Saltzman.

To the students, it was awesome. “I really liked standing in the place where many of the ships from World War II were made,” said Theo. Birdie, another student, closely studied a robotic pigeon used in “The Producers,” a movie shot at the Yard, and found it “amazing.” Sebastian was thrilled to see models of all the ships built there, including some that made history — the battleship USS Maine, which sparked the Spanish-American War in 1889; the USS Arizona, which sank during the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941; and the USS Missouri, onboard which Japan signed an unconditional surrender to end World War II.

Evans-Lora said the trip connected to many areas she and the students had studied in class, from science and simple machines to collaboration and historical figures, including President Theodore Roosevelt, who also served as assistant secretary of the Navy. It was about innovation and invention, constants at the Yard and in the borough of Brooklyn.

Class trips to Building 92 of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, organized by the Brooklyn Historical Society, are free thanks to funding from the Yard.