With spring’s arrival, we enter field trip season in schools. Curriculum trends come and go, but field trips have been a mainstay of K–12 education for decades. Trips are fun excursions and provide a break from classroom learning. They also impart myriad benefits for students, including honing social skills, fine-tuning observational skills and demonstrating real-world applications of school subject matter.

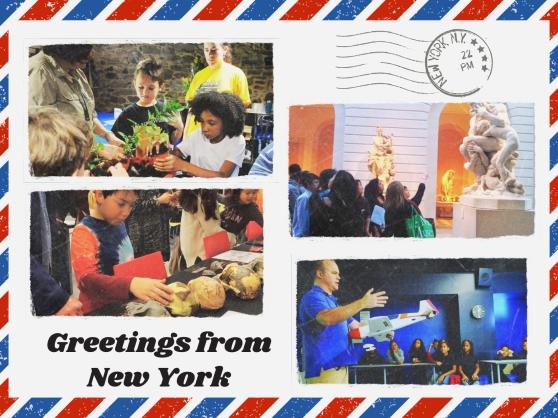

Being in New York, we are fortunate to have an abundance of world-class destinations that are age-appropriate, meet a range of student needs and can be linked to every subject area.

I grew up in New York City and clearly remember field trips from my childhood. In fact, knowledge retention is one of the key reasons that trips continue to be popular.

“Certain experiences really stick with students,” said Ruth Duran, a 6th-grade teacher at PS/MS 315 in the Bronx. Field trips, she said, help learning become “ingrained in their brains. When you can tie learning to a particular memory, it becomes more than just facts in a classroom.”

But planning a field trip in New York City is no easy feat. The Department of Education’s school trip guidelines can be found on its InfoHub. But beyond those requirements, seasoned professionals like Lauren Couto, a middle school science teacher at Jonas Bronck Academy in the Bronx, strategically plans with her class and her chaperones to help things go smoothly.

Before each field trip, Couto makes slides for her students with pictures to clearly explain where they are going, why they are going, the day’s schedule, what to wear and bring, and behavior expectations. Sometimes she’ll offer a small reward to the class that brings back their permission slips first.

Each chaperone gets a detailed trip plan with contact numbers, bus and trip groups, and a map of their destination. She always makes a group chat with chaperones so everyone is reachable. A chaperone from each bus obtains the driver’s number, confirms pick up times and takes a photo of the bus so it can be easily identified at pick up. Couto travels with plastic bags in case someone gets sick on the bus, and she brings golf pencils if students need to complete writing or worksheets on the fly.

Despite all these preparations, Couto said to “expect things to not go as planned.” She advises not to get stressed out about things that are beyond your control. “Even if a trip gets cut in half, it can still be a fun, memorable experience,” she said.

“The city is your classroom,” is the motto of A School Without Walls in downtown Manhattan. The high school combines a virtual program with classroom learning and frequent trips the staff refer to as “fieldwork.” “We want our students to be out exploring the world and what our local communities offer,” said Sarah Hanson, the school’s ENL and French teacher.

The fieldwork is deeply connected to the school’s curriculum: For instance, a lesson on fast fashion led to a visit to a recycling center in Queens, while seeing “SIX” on Broadway was interwoven with a study of feminist culture. Trips are usually scheduled to take place after about two weeks of establishing extensive background knowledge.

Experiences outside the classroom remind students that learning “isn’t constricted to school hours or classroom spaces,” said Hanson.

Managing student behavior on a field trip can also be a challenge. Before a trip, Lindsay Melachrinos, a 6th-grade science teacher at the Computer School in Manhattan, gives her students a clear sense of what they are going to see and why. “The more they know about what they will experience, the better,” she said. “Surprises are the enemy of good field trip behavior management.”

Melachrinos also tries to find a balance between offering the kids a fun experience and keeping them on track by assigning a task for them to complete.

Field trips also help students understand appropriate behaviors for different settings. Duran regularly takes her middle school students to the Metropolitan Museum of Art when they are studying mythology. They visit the Greek and Roman wing where most of the statues are nude.

Part of the prelearning, she said, is how to “admire the art without being embarrassed about it.” Having these discussions beforehand, Duran said, sets the expectations for students’ behavior and has prevented inappropriate comments during the visit.

Field trips expand students’ horizons. “Not everyone has the opportunity to visit cultural institutions in their free time,” said Couto. “Class trips get kids out of their neighborhoods and expose them to new places.”

Duran said her trips throughout the city have encouraged the students at her Bronx middle school to apply to high schools in other boroughs. She said students come away from field trips with this knowledge: “I can go beyond my borough and go out into the city, and it’s OK because I’ve been there before.”

Indeed, these field trips reinforce to students that New York City is theirs to explore and inhabit.

“We are teaching future adult New Yorkers,” said Melachrinos. “Every trip is a chance to know and love our city and to practice being an active and engaged citizen.”

Duran said she wants her students to know that “even if you are a student at a Title I school in the Bronx, you belong in all of these places, and they are yours to visit.”

She wants her students not to be afraid of new places, and field trips break down that fear of the unknown.

“It’s a whole big world out there,” she said. “So go forth!”