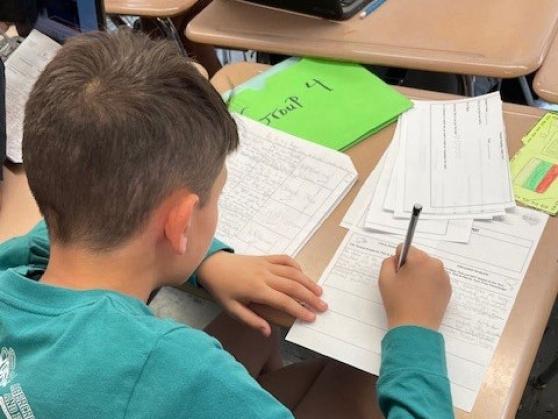

Strategies like journaling (above) and social-emotional prompts can help students make the leap to making inferences in fiction and non-fiction.

A major turning point in reading instruction is the shift from literal understanding to inferential textual analysis. This leap can be challenging: Students often resist making inferences because “those ideas are not in the text.” In my 12 years as a middle school ELA teacher, I’ve hit on several strategies to help students develop their inference skills, which has a significant impact on their literacy development.

Social-emotional prompts: Begin lessons with a self-awareness question about the topic. Asking such a question will build students’ background knowledge and help them personally connect to the text they are reading, which is important because personal connections are the foundation of inferential textual analysis. For example, in “A Long Walk to Water,” a novel by Linda Sue Park that I use in my 7th-grade ELA class, I begin the lesson for Chapter 2 by asking, “How does the setting of your home life or your social life shape the way you behave?”

You can end the lesson with a self-awareness “wrap-up” question. These questions can be text-to-self or text-to-world connections that will continue to build students’ inferential analysis of how the text affects their understanding of themselves or the world around them.

Double-entry journals: I provide my students with “double-entry journals” to make a side-by-side analysis of plot points in the text and how those plot points develop their understanding of turning points or character development. The left side of the double-entry journal is titled, “Literal: Ideas Directly Stated in the Text.” The right side is titled, “Inferences: Ideas NOT Directly Stated in the Text.” For example, in Chapter 2 of “A Long Walk to Water,” a student might write on the literal side, “Nya is in pain but is still carrying the water for her and her family’s survival,” and on the inference side they might write, “This shows her brave character.” For examples of how to use double-entry journals, check out Kelly Gallagher and Penny Kittle’s “180 Days: Two Teachers and the Quest to Engage and Empower Adolescents.”

Reader’s notes: For read-alouds, I provide reader’s notes for each chapter in a graphic organizer that asks literal questions, inferential questions and evaluative questions, with a space for students to write answers. This set of questions helps scaffold the leap from literal understanding to evaluative analysis. Reader’s notes are particularly beneficial for English language learners and students who are two or more grade levels below reading level.

For short stories, informational texts or a short chapter of a novel, each lesson takes two 45-minute single periods or one 90-minute block. I read the text aloud first to model fluency and pronunciation. A second read-aloud is done with peers — either partner reading or whole-group reading. During the second read-aloud, students answer the literal questions together. Students then answer the inferential and evaluative questions independently.

I ask students to discuss their responses to inferential and evaluative questions with fellow students. Through this turn-and-talk exercise, the students learn that unlike the literal questions, inferential and evaluative questions can have more than one plausible answer.

Tina Macchio is an ELA teacher at IS 141 in Astoria, Queens.