Class struggles: The UFT story, part 8

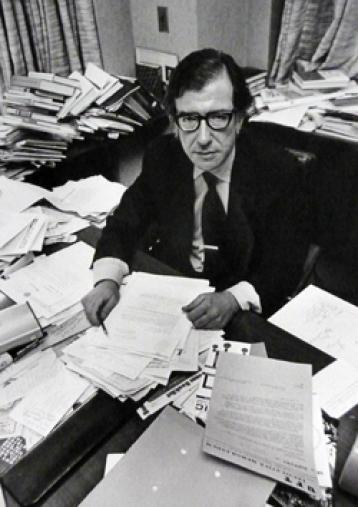

Al Shanker at his UFT office.

by Jack Schierenbeck

Not far from the UFT’s Park Avenue South headquarters, Al Shanker sits stiffly in the study of his apartment. Physically, he’s not himself.

For months now he’s been fighting for his life. A cancer he thought he’d beaten a couple of years ago has come back with a vengeance, sapping his legendary workhorse stamina. A toxic one-two punch of chemo and radiation hasn’t poisoned his spirits, though.

With relish he recalls his life and work. He takes special pleasure in the story of the evening high school strike that never was.

The year was 1965. Just months into his first term as UFT president, 36-year-old Shanker faced his first real test in office.

There were rumblings that the evening high school teachers would walk off the job. Five years before, many of the same instructors had staged the first work stoppage in the history of the city’s public schools. Shanker, a Queens junior high teacher and member of the Teachers Guild, the UFT’s predecessor, had stood alongside them.

Within a few weeks the city had caved in, almost doubling the teachers’ pitiful $12-a-night stipend. The evening uprising, as it turned out, was the spark that helped jump-start the city’s teacher union movement.

His way or the highway

This time around, though, Shanker wasn’t cheering. Roger Parente, a key figure in that pivotal 1959 strike, was demanding that the evening high school teachers have the right to negotiate a separate contract, grievance procedure and seniority protection — this at a time when the UFT was close to getting Board of Ed recognition as the sole bargaining agent for all part-timers.

Here we go again, thought Shanker, fearing a return to the days when more than a hundred-odd teacher organizations pulled every which way but together. Besides, here was a leader of the opposition — who had lost his bid to become UFT president — looking to start a rival union when fewer than half the teaching staff were card-carrying UFT members. This had to be stopped.

Shanker set up a meeting at Wadleigh JHS to speak with evening high school teachers. He arrived at the Manhattan school only to find an ambush. Sitting there ready to debate him was Parente. A tape recorder was thrust under his nose and he was told he had 10 minutes to state his case.

Shanker would have none of it. He told them in no uncertain terms that he had asked for the meeting and wasn’t there to debate. “I am not speaking for 10 minutes. I am going to speak for an hour. This is my meeting. Meet with [Parente] if you like, but not at this meeting.”

Shanker warned that an unauthorized walkout could domino into a series of wildcat strikes by other groups — and blow the union’s credibility and the public’s faith in collective bargaining. Public officials had to know that a signed contract meant labor stability, not anarchy. Worse, the strike would be a strike against the UFT. “I told them that the union was going to win all these things in the next contract and they could have a committee within the organization.”

Then Shanker dropped the bomb.

“‘I will tell you what I will do if you have this strike,” he recalls warning. ‘I will personally enlist thousands of teachers to take your jobs and I will be one of them. We will march through your picket lines because you will be striking against the UFT and against unity. We will not only take your jobs but if the Board of Ed ever reinstates you, we will shut the day schools in the city down.’”

Shanker would make the same speech at all 16 evening schools. The teachers got the message. There was no second evening high school strike. And, as promised, not long after the UFT did win the right to represent the evening people.

Rough beginnings

To those who know him, the story is vintage Shanker. To admirers it represents the kind of savvy, forceful use of executive power without which the UFT could have broken apart in internal squabbling or been overwhelmed by outside forces. “Al seemed to work [cold-bloodedly],” remembers Sandy Blair, a longtime Shanker ally. “He would go right for the jugular and just rip it open. And I liked that. Still do.”

To others, though, the anecdote would no doubt confirm Shanker’s reputation as ruthless and power mad. “He’s the evil genius of American labor,” said one longtime enemy, who thought better of being named.

Strong leader or strongman — or both? Love him or loathe him, fans and haters alike acknowledge Al Shanker was not someone you wanted to pick a fight with.

At any rate, Parente and the rebel evening school people were neither the first nor the last to feel the legendary Shanker sting. Combining erudition — only an unfinished dissertation separated him from a Columbia University doctorate in philosophy — and a stiletto tongue, Shanker could slice and dice arguments with the best. Then again, he had had some good teachers.

Al Shanker grew up the only Jew in an Irish and Italian neighborhood, where reminders of tribal enmity were frequent and none too gentle. Born on Manhattan’s Lower East Side on Sept. 14, 1928, Albert was a toddler when he was taken across the East River to the bleak factory-town landscape of Long Island City. Speaking only Yiddish and keeping kosher, the Shankers found the Irish-Catholic stronghold a world apart.

Ever since the tidal flood of Eastern European immigrants at the turn of the century, anti-Jewish feelings had been simmering. No less a personage than automobile pioneer Henry Ford used his fabulous fortune and influence in the 1920s to spread the idea that “The International Jew” had hatched a plot to take over the world. With the deepening of the Great Depression, though, New York fell victim to an especially rabid strain of anti-Semitism.

Egged on by Father Charles Coughlin, whose national radio broadcasts and newspaper Social Justice regularly blamed “Jewish bankers and merchants” for the world’s economic woes, groups like the Christian Front and the Christian Mobilizers terrorized Jews. These mostly Irish thugs roamed Jewish neighborhoods like the South Bronx, smashing storefront windows and vandalizing synagogues and cemeteries.

To be sure, there were those among the Irish like lawyer and politician Paul O’Dwyer and labor leader Mike Quill who spoke out against the bigotry, but to little avail. Even within the top ranks of Quill’s Transport Workers Union, many urged him to remain silent. And the Irish-dominated police department usually ignored Mayor LaGuardia’s orders to end the persecution.

Almost 60 years later, Shanker vividly recalls Coughlin’s anti-Semitic ravings blaring from apartment windows on Sunday mornings. He remembers that as a child he sat for hours on the footbridge of the Queensborough Bridge, gazing into the East River and wondering “what we Jews had done to make everyone so mad at us. And what is it that Jews could do to make them more attractive and less odious to others.”

Already a gangly six-footer at 11, Shanker made a big target. “I could never play with the kids. There was always this ‘Jew boy’ and ‘Christ killer’ stuff. If I tried to go out and play I’d get beat up.

“The little kids could take me on. ‘Watch this,’ they’d say, ‘we can beat up the biggest kid on the block.’ It was very painful.”

Shanker was the child of immigrants from Czarist Russia. His father, Morris, delivered newspapers seven days a week — starting his day at 2 a.m. “He’d get back at 7 in the morning, totally exhausted,” remembers Shanker. “Then at 10 o’clock the afternoon papers would come out, and he’d start all over.

“Imagine in the snow and heat all those pounds and pounds of paper in a pushcart, climbing 5 or 6 flights of stairs to deliver a two-cent newspaper. He worked like a beast.”

‘Unions were just below God’

His mother worked, too, upward of 70 hours a week bent over a sewing machine in hellish sweatshops. “The windows and the doors were locked,” Shanker recalls, “because [the owners] were afraid the workers would take a shirt or pair of pants or throw them out the window to a friend. There were no benefits.”

But Mamie Shanker was an ardent member of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union and the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. It was through the labor movement that the work week was whittled down, conditions improved and benefits and a pension won. “In my home,” Shanker said, “unions were just below God.”

That Al Shanker even survived his harrowing childhood in one piece — no less became a teacher and labor leader — is a tribute to his mother and grandmother, Rachel Burko, who shared the cramped apartment. “I was the apple of my grandmother’s eye,” said Shanker, who has a younger sister Pearl. “She was forever buying me candy or whatever I wanted. I was named after her deceased husband and she would say I was destined for very important things in the world.” From his mother he inherited a gift for words and an appetite for argument. “My mother was a person who constantly engaged me. We had a deal. I would tell her everything and in exchange, no matter what I did, she wouldn’t punish me. So I had to defend my positions constantly. When I landed a really good argument she would just break out laughing.”

Try as she might, however, his mother couldn’t protect him from the outside world. “My mother tried all sorts of things. She tried paying some of the kids to teach me how to play ball. They would teach me for a half hour and then beat the hell out of me.”

His mother drew the line, though, when an upstairs neighbor approached with a proposition that the Shankers pay her son 25 cents a week to protect Albert. “My mother was no fool. She knew she’d soon have half the neighborhood on the payroll.”

Surrounded by so much hostility, the boy became a virtual prisoner in his own house. “I would just go berserk because I had nothing to do,” he recalled. He managed to keep his sanity by listening to the radio and collecting stamps. But it was in the Boy Scouts that he came into his own — though not until after being denied admission to one troop because of its affiliation with a local Catholic church.

Early successes

“Here I was being recognized for what I could do, rather than the Jew boy stuff,” Shanker said. “So it was very important.” As if to punctuate the point of how much the scouts meant to him Shanker ambles over to a wall of crammed floor-to-ceiling bookcases and immediately locates a copy of the Boy Scout Handbook. Tenderly, he touches the weathered pages as he recalls boyhood tales of hiking and camping. But it was also in the scouts that Shanker had his “first successful politically rebellious experience.” Early on he challenged his scoutmaster over the amount of time the troop was spending doing military drills. “I drew up a petition that called for less march and drill and more camping and hiking.” The scoutmaster agreed. Later, when the man was drafted into the military, he designated 14-year-old Albert acting scoutmaster — going so far as to issue him a rubber stamp with the scoutmaster’s signature so he could test the other scouts.

Shanker also showed an early flair for organizing — boosting the troop’s enrollment from 17 to 85 and adding a Cub Scout chapter.

It was also around this time that Shanker passed the competitive exam for Stuyvesant HS and discovered yet another escape route. “It was a whole new world now. It was not the gang atmosphere. [Stuyvesant] was a bunch of bright kids from all over the city. It was an intensely competitive school.” He flourished — getting 100s on his math and chemistry Regents. As the head of the school’s debating team, one student remembers Shanker was so convincing that he could “take the side of the Arabs and win” — all the more remarkable when you consider he’d entered 1st grade speaking nary a word of English.

After graduating from Stuyvesant in the top fifth of his class, Shanker took the unusual step of going off to the University of Illinois at Champagne-Urbana.

It wasn’t long before he found out that anti-Semitism wasn’t just the residue of New York’s ethnic cauldron. When an on-campus housing shortage forced the 18-year-old freshman to look for a place to stay off campus, the pickings were slim. More often than not, ads for rooms carried the tag “No Jews or Negroes Wanted” or “White Anglo-Saxon Protestants Only.”

When he did find a place to stay, it was at a farm several miles outside of town. Shanker made do, getting back and forth on a bike.

In the Champagne-Urbana of the late 1940s, Jews weren’t the only pariahs. Coming from New York City, Shanker recalls being surprised by the overt racism. Blacks still could not eat in restaurants that catered to whites. Surprised and moved. So much so that he joined an interracial group at a local Unitarian Church that used sit-ins and court action to help put an end to such open displays of discrimination. Still, he was hurt when Unitarian students made his being a Jew an issue when he ran for office.

Shanker found greater acceptance in left-wing circles where he became the chairman of the campus socialist study group and a member of Young People’s Socialist League. “I was a socialist of different stripes at various times — [even] a Marxist for a short period of time.”

A good, catch-all theory

For someone trying to figure out why the world had so much injustice, the attraction made perfect sense. “Here I was as a kid growing up spending lots of my time thinking about the injustices against myself, my family, against Jews, poor blacks, the workers and so forth. Well, socialism basically provided a theory why all this was happening. It’s a good catch-all. Whether the theory is right or wrong is something else. You still feel comforted... . It’s like a religion.” Though Shanker would eventually fall away from the church of the popular insurrection, he did, at the age of 29, name his first born, Carl Eugene, after those revolutionary scions Marx and Debs.

Although he briefly, during high school, “got sucked into being pro-Soviet,” Shanker’s lifelong hatred of Soviet-style communism began while still a teen.

Reading “Homage to Catalonia,” George Orwell’s searing first-person account of the Spanish Civil War, was sobering. Orwell had gone to Spain naively believing that the Soviet Union was standing up for the workers’ democracy only to find that Stalin had something else in mind.

“Here was Orwell, this innocent leftist,” says Shanker, “who wants to fight the fascists, but the Communists will stop at nothing, including wiping out the non-Stalinist opposition, to make sure they alone emerge in control. It was a classic case of rule or ruin.”

Later, Orwell would leave another dent in young Shanker with his devastating satire of barnyard communism, “Animal Farm,” published in 1946. In the same year he read Jerzy Glicksman’s “Tell the West,” one of the first exposés of the Soviet gulag system. Shanker invited the ex-communist Pole to be a guest speaker at the University of Illinois, where the two struck up a friendship.

Still a teen, Shanker recalls buying newsstand copies and later subscribing to Partisan Review, a journal of “socioliterary criticism” put out by a mostly Jewish group of left-wing, anti-Stalin, New York intellectuals. He also remembers how taken he was by Dwight MacDonald’s anti-authoritarian and bohemian brand of cultural anarchism found in MacDonald’s magazine Politics.

Like many on the “Non-Communist Left,” Shanker still held fast to the notion that the Soviet system amounted to a “betrayal” of Marx and socialism. Over time, though, he came to see that the so-called “excesses” of Stalinism “weren’t just about Joe Stalin. It was a systemic thing … you had to heed the warnings of the Founding Fathers about limiting the powers of government: That if the government had these huge powers, you couldn’t restrict these powers to do things that were only good.”

Still, aside from his hardline anticommunism, Shanker’s leftist politics were always of a practical kind. Not one to tilt at windmills, he realized early on that socialism in the U.S. was going nowhere. “I always had this pragmatic side,” he said. “I knew that the Socialist Party was not going to elect a president of the United States. But you had a Democratic Party which was more liberal and stood for at least some of the things socialism stood for. So the thing to do was to operate within the Democratic Party.”

After graduation from Illinois, Shanker returned East to attend Columbia’s graduate school of philosophy. With him was his college sweetheart and wife, Pearl Sabath, from Rock Island, Ill. While she settled into public school teaching and he a doctoral program, the country was anything but settled.

No to communism and McCarthyism

For the second time in 30 years the United States was in the grip of a Red Scare panic. In early 1950, Wisconsin Sen. Joseph McCarthy had charged that the State Department was overrun with “members of the Communist Party” in his infamous “I have here in my hand a list...” speech.

Not long after, in June, there were more shockwaves as communist North Korea invaded South Korea, soon followed by the arrest of a Brooklyn couple, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, accused of passing atomic secrets to the Russians.

“It was horrible,” Shanker remembers thinking at the time. “It had a chilling effect on the whole country, everything from newspapers and books to movies. In the classroom teachers were afraid to deal with controversial subjects. It was very frightening.”

What worried him was that the resulting hysteria was giving free reign to the old Father Coughlin-like right-wingers, fascists, anti-Semites and union-haters who had never stopped reviling “Rosenvelt’s Jew Deal.”

Still worse in his mind, was that by trampling civil liberties and equating dissent with sedition, American anticommunism had assumed some of the worst features of the authoritarian rule it was suppose to revile. In other words, said Shanker: “McCarthyism was giving anticommunism a bad name.”

To Shanker communism was no idle threat. The country did need to protect itself from Soviet spies and internal subversives, but not at the cost of blacklisting actors and writers. Teachers, however, were another story. While at first opposed to any ideological litmus test that would have barred communist teachers from the classroom, Shanker remembers attending a debate at Columbia that changed his mind.

Historian Henry Steele Commager made the classic First Amendment, hands-off, academic freedom argument. Philosopher Sidney Hook, on the other hand, maintained that academic freedom should not protect those whose sworn allegiance is to a system that puts party loyalty before academic freedom and the search for truth.

“Hook wiped the floor up with Commager,” remembers Shanker. Asked if he would have voted with the majority in the Teachers Guild’s Delegate Assembly in 1950 which voted to ban communist teachers, Shanker answers “probably.” Speaking at a conference on the history of New York City teacher unionism in the spring of 1995, Shanker left no doubt about where he stood on communists in the classroom. “These are not independent minds,” he said point blank. “These people are not looking for answers. They know the answers.”

Lately, he’s not so sure. Shanker has been rethinking the question and wonders out loud whether it was fair to single out Communist teachers when it’s clear that they have no monopoly on robotic, blind obedience to authority. “Take Orthodox Jews and Catholics, for example,” he says dryly.

At any rate, Columbia’s ivory tower wasn’t the worst place to ride out the McCarthy storm studying the likes of Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, Hegel and Dewey.

As it was, Shanker sailed through his coursework, passing both of his preliminary examinations before embarking on the writing of his dissertation.

As it turned out, Albert Shanker never wrote that doctoral thesis. Broke, feeling a bit school-weary and with university-level philosophy jobs practically nil, he became a city school teacher. The year was 1952 and his first assignment was as a substitute at PS 179 in Manhattan’s East Harlem.

“It was a lousy job,” said Shanker, who is forever retelling the time he came home shaking his head and complaining that his new job left no time for a real lunch. “Teachers are so smart they’re stupid,” Mamie Shanker told her son. “They don’t realize that they have to have a union.”

Shanker still the head of his class

It is a rain-soaked Saturday afternoon and I’m making small-talk with Al Shanker about his taste in eyewear. Why, I ask, did he switch from wire-rim to his trademark black, thick-frame glasses? “I started being on television a lot and George [Altomare] said wire-rims made me look shifty,” he answers.

Ah, so that explains the “Buddy Holly look,” I tell him. He stares back blankly.

“Buddy Holly, the ’50s rock-n-roll star who was killed in the plane crash. You know, Peggy Sue?” I say incredulously. Still nothing.

“He’s kidding, right?” I ask Eadie, his wife of some 35 years.

“He’s not,” she says seriously. “Al barely knows Elvis.”

By now Shanker is smiling. “You see, when it comes to cultural literacy… .”

Pop culture icons aside, there aren’t many subjects Al Shanker can’t hold forth on. A voracious reader, he can give you the gist and a critique of a book he read 40 years ago. Listening, you can’t help but think that had Shanker stuck to the university path he would have run one high-powered graduate seminar.

He’s bookish, all right, but there’s much more to him. Over the years Shanker’s passions have included photography, baking and wine-making — he’d buy grapes by the bushel for pressing and keep up to 300 gallons of wine aging in barrels in his basement. An audiophile extraordinaire, countless union comrades will tell you about the time he spent setting up their home stereo systems.

‘As I was saying …‘

But, in the end, it’s Shanker’s almost extraterrestrial mind that grabs you. Take the day I visit him at Sloan-Kettering Memorial Hospital. At his bedside are books by the educational-reform guru E.D. Hirsch and Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm — he seldom reads fewer than two books at a time. With the bags of therapeutic “potion,” as he calls it, slowly emptying into his veins, Shanker and I begin what was to be about a three-hour interview. Naturally, we’re interrupted no fewer than a dozen times by hospital personnel and telephone calls, some lasting as long as 10 minutes.

Each time, I push the pause button on the tape recorder and, so as not to appear as if I’m eavesdropping, stare at the ceiling or out the window. Invariably, within a minute or so, I would forget where we were in the conversation. Not to worry. No matter whether he’d been interrupted in mid-sentence or mid-thought, Shanker never once asked, “Now where was I?” Instead it was always: “As I was saying.” This kind of clarity of mind even shows up in the way he listens. In response to my overly long, wordy and sometimes disjointed interrogation, he’s able to tease out a central thesis or at least a good question, saying, “If you’re asking me whether… .”

As for Shanker’s answers, well, they’re anything but stock. Talking with him you never get the feeling he’s searching the hard drive for some old file — a rare quality in a world where public discourse has been dumbed down by fortune cookie sound bites and pat answers. And sometimes after rolling an issue around in his mind he’ll actually say, “I don’t know.”

A former Daily News reporter who covered Shanker for years says: “He’s a fresh thinker. Here he is, close to 70 years old and still searching.”

Shanker, he said, had a reputation among reporters for straight answers, sometimes to a fault. “The guy just hates PR. He’s so honest it used to get him into trouble. Say what you want about Al, he’s a mensch.”

Originally published in New York Teacher, January 13, 1997