Class struggles: The UFT story, part 6

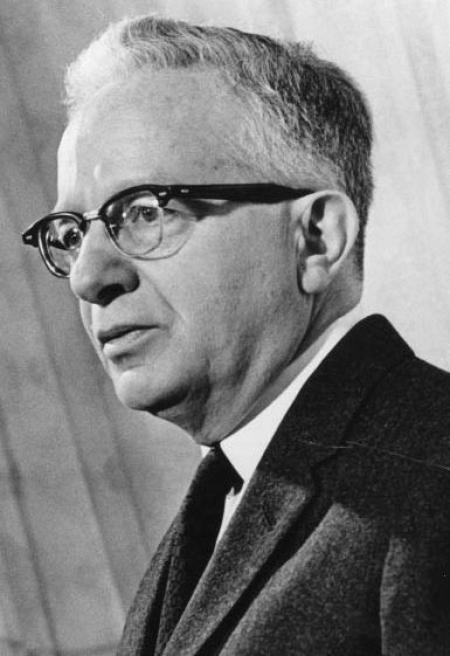

Charles Cogen

by Jack Schierenbeck

For Milton Pincus, the decision to call off the November 7th strike in return for Mayor Robert Wagner’s promise of a fact-finding committee loaded with the leading lights of the city’s labor movement, was a no-brainer. From where he stood — outside Brooklyn’s Tilden HS walking a lonely picket, one of only 14 teachers out of Tilden’s 300 or so faculty — the strike was a loser.

“[It] could have been a total disaster,” Pincus recalled years later as part of the UFT Oral History Project. “[The city] could have destroyed those few thousand who went out. But because of Dubinsky, Potofsky and Van Arsdale — and the influence they wielded with the city officials — they prevented a massacre.”

Pincus wasn’t alone in reading the appointments of David Dubinsky and Jacob Potofsky, presidents of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, respectively, along with the powerful head of the New York City Central Labor Council, Harry Van Arsdale, as a sign that things were looking up for the fledgling UFT.

But if Pincus had breathed a sigh of relief at the news of the settlement, Roger Parente had breathed flames. Long leery that close ties to the city’s labor movement, which was wired to the Democratic political machine, would dampen teacher militancy, Parente had felt the strike was just catching fire when the labor patriarchs snuffed out the blaze.

At a closed-door meeting, Parente, a UFT vice president, had pleaded with Van Arsdale for one more day to show that the strike was starting to gel. The city’s Central Labor Council president, worried that the walkout was hurting the mayor, not only said no, but also threatened to disavow the strike altogether if it weren’t halted immediately.

“The thought that our actions could be vetoed by others who knew nothing about education did not sit well with me,” Parente told the UFT Oral History Project in 1985.

Bailout or sellout, there would be a rude awakening for anyone who thought that even a blue-ribbon panel with a prominent union label could deliver collective bargaining on a silver platter to the UFT.

Winning the right to represent all the city’s teachers at the bargaining table would take 13 months, a referendum, a bargaining election, a battle royal with the powerful National Education Association, stonewalling, scandal and a bloodletting at the Board of Education, the strong backing of the American Federation of Teachers, an angel named Walter, a spook named Dave and countless thousands of hours of organizing by hundreds of union volunteers.

With the exception of Philip Taft’s “United They Teach,” histories of this period all too often give only passing mention, sometimes barely more than a footnote, to this year-long struggle for recognition. “No one will ever know the story of what it took, the sweat and sacrifice that went into winning,” said George Altomare, one of the authors of that struggle. “The [November 7th] strike is what everybody remembers, but it would have meant nothing if we’d lost the other fights.”

Board was in no hurry

As it was, it took only two months for the Dubinsky, Potofsky and Van Arsdale committee to deliver its report recommending an “election before the end of the school term.”

The board, however, was in no hurry. Both board members and Superintendent of Schools John J. Theobald were still miffed that Mayor Wagner had gone over their heads and brokered an end to the November strike. As they saw it, the mayor had overstepped his authority in promising their employees collective bargaining. They were intent on reasserting their authority and making the mayor, his labor cronies and the upstart UFT sweat.

Besides, in their minds, the final strike tally — 10 percent of the teachers went out — was hardly a mandate for action. The vast majority of teachers was yet to be heard from, especially the dozens of teacher organizations that effectively would be out of business if the UFT were granted exclusive bargaining rights. They questioned whether it was even legal to grant exclusive bargaining rights to one organization.

Why shouldn’t other organizations, which had not struck the system, be entitled to a piece of the action through “divisional bargaining” — that is, separate bargaining for elementary, junior high and high school teachers? For that matter, why not boroughwide bargaining?

To buy more time and sort out these issues, the board appointed its own Commission of Inquiry on Collective Bargaining. Several months later the Commission proposed taking a poll of teachers to determine how they felt about collective bargaining, the results of which would be binding.

That wasn’t what the Board of Ed had in mind. Balking at the idea of being bound by the results, the board rejected the recommendation of its own committee, which promptly resigned in protest. Instead, the board insisted that the city’s Board of Estimate — the now disbanded panel composed of the mayor, comptroller, city council president and five borough presidents, — should have the final authority to nullify any collective bargaining agreement.

Still, under pressure from the mayor, who was facing a tough reelection fight that November, the Board of Ed set aside June 19-29 for a poll of teachers. The referendum asked one simple question: “Do you want collective bargaining?”

Battling the NEA

Leading the charge against collective bargaining was the National Education Association. Founded in 1857, the NEA was a powerhouse on the national scene, with a membership of over 700,000 — almost 12 times the number of AFT members. However, the NEA had only 700 members in New York City schools in 1961.

What it had, though, was a considerable war chest which it didn’t hesitate to tap. Dozens of organizers were detached to the city to help mobilize opposition to collective bargaining and the UFT. Using a front called the Teachers Bargaining Organization (TBO), the NEA brought together a coalition of teacher organizations — most prominently the elementary and secondary school teachers’ associations — that were dead set on stopping the UFT.

In public hearings NEA/TBO spokespersons warned that teacher ties to organized labor and the use of strikes were unbecoming of “professionals.” “Illegal” strikes, said the TBO, undercut a teacher’s “responsibility for inculcating respect for the institutions of democratic society and adherence to the laws.”

At a Board of Education hearing in late 1960, the director of the NEA’s New York office urged that “no organization be eligible for nomination as bargaining representative unless it gives complete assurance that it will adhere to the law and that it will not call its members into strikes.”

The NEA/TBO literature was more blunt. In a publicity campaign designed to heighten the fears of teachers about labor affiliation, handouts routinely referred to “corrupt and autocratic union bosses.” One leaflet asked: “Do you want Hoffa and Bossism?” Another urged teachers to vote for the TBO “run by teachers for teachers — not under the thumb of any labor bosses.”

The UFT did its best to quash talk of union “bossism” and “corruption” as “[John] Birch-type smears,” and “scare talk.”

But the NEA wasn’t raising these charges in a vacuum. The undeniable fact was that by 1961 unions had a pretty bad reputation. Some of labor’s sorry image was the handiwork of the press — wealthy and often with labor troubles of its own — which seldom had a kind word for unions. Writing more than 50 years ago, maverick journalist A.J. Liebling observed that labor reporting painted a composite picture of unions as “stubborn, selfish, unreasonable, overpaid, grasping, domineering, un-American, inefficient, undemocratic and gangster-ridden.”

But not all of labor’s public image problems were a fiction. Stories of hoodlums running unions, ransacking pension funds, muscling businesses and strong-arming dissidents had more than a grain of truth. The Teamsters, after all, had been expelled from the AFL-CIO in 1957 for mob connections while the much-publicized, three-year-long Senate McClellan Committee had uncovered ties between the underworld and the longshoremen’s, garment and construction trades unions. By the early 1960s then, the NEA’s anti-union stands and appeals for “independence” might have been expected to play well among teachers.

In the end, though, they didn’t. Despite its deep pockets and appeals to even deeper prejudices, the NEA proved to be no match for the UFT.

For one thing, the NEA had a hard time pinning the label of labor “boss” on the union’s most visible presence, its president, Charles Cogen.

Barely five-foot tall, soft- and well-spoken, Cogen was the antithesis of the gruff, bare-knuckled, dese, dems and dose stereotype. A lawyer and a member of the state bar association, Cogen’s character and integrity were beyond reproach. Never having taken even a dime from union office — he took subways everywhere to save money — no one could ever accuse Cogen of looking for an easy meal ticket. Nor could it be said that he wielded a heavy hand within the union. Just the opposite: His loose, inclusive style bordered at times on the anarchic.

Try as they might, the NEA and the other critics of the UFT would be hard pressed to come up with any dirt on Charlie Cogen. Still, it would take more than one leader’s luster to defeat the NEA. It would take a movement. And that it was.

“We were like an army of ants,” Altomare recalled, explaining that it took hundreds of volunteers to do the massive outreach campaign. Just reaching teachers, he explained, was no small task. Back then there was no labor law requiring employers to furnish the names and addresses of employees to unions.

Now and then a friendly school secretary would turn over the roster. But the only other source of names was the city, which was required by law to keep up-to-date lists of the names and addresses of its employees at the Municipal Library.

Caught copying

The idea of hand-copying the names of 45,000-plus teachers was quickly discarded in favor of photographing each page. But since cameras were forbidden in the Municipal Library, the operation would have to be done undercover. It took days — and a couple of times of being thrown out — but Sy Solomon, a junior high school teacher and a photographer for the union newspaper, got the job done. [See profile below.] Getting the names was only the beginning. Next came the mind-numbing, painstaking work of poring over the lists, often with magnifying glasses, looking up tens of thousands of phone numbers, mimeographing literature, hand-printing addresses on envelopes, licking stamps, working the phones to energize the committed and persuade the doubters.

Leo Hoenig got plenty of practice polishing his “pitch” as one of the UFT’s telephone operators. For months, the social studies teacher at JHS 168 in Queens, spent his evenings and weekends holed up at Central Labor Council’s Manhattan headquarters making calls. Both the Labor Council and the ILGWU had donated their telephone banks to the campaign.

“My life was spent at the union,” said Hoenig recently. “We all knew each other. It was like a family.”

Said Altomare: “We had the spirit, the camaraderie and we had the truth.”

They also had Dave Selden, whose gift for cloak-and-dagger intrigue was near legendary. In his memoir, “Teacher Rebellion,” Selden tells of how, in exchange for a union card in a craft union and money for “expenses,” he acquired a mole inside the NEA’s New York office. The spy, wrote Selden, kept him “informed of every move of the NEA, sometimes within minutes of the time the decision had been made.”

Thanks, also, to friendly union printers, mimeographed materials from the NEA office found its way into UFT hands.

Undercover operation

The Selden touch went beyond snooping. In his book, “Power to the Teacher,” Marshall Donley writes that UFT operatives were so adept at dirty tricks that the hapless NEAers didn’t know whether they were coming or going — literally.

Writes Donley: “Members of the NEA task force scheduled to speak at one of the city schools often were notified by telephone that their schedules had been changed, only to find when they showed up that school was out and teachers had long since departed for home, or the addresses given them were not schools but vacant lots.”

The results of their work was stunning. With the UFT standing alone as the one teacher organization urging a “yes” vote, teachers voted yes by a three-to-one margin — 27,367 to 9003.

Still, the Board of Ed did nothing.

As it turned out, the board’s days of stalling or much else were numbered. That summer, 110 Livingston Street was rocked by scandal. A state investigation uncovered evidence of payoffs, bribes, shoddy construction, slovenly oversight and mismanagement in city school construction funds. Even Superintendent Theobald was tainted when it was revealed that vocational high school students had built him a 15-foot boat in a shop class. The city’s papers immediately took to calling him “admiral.”

The board, with a little push from Mayor Wagner and the UFT, toppled. At a special session called by Governor Rockefeller in August 1961, the state Legislature ousted the nine-member panel.

By late September a new board was in place. Its makeup could hardly have been better from a UFT standpoint. It even had a representative from organized labor, Morris Lushevitz, secretary of city’s Central Labor Council.“

They were very eager to do the right thing,” said Albert Shanker. “This was a liberal, Democratic, pro-union bunch of people who felt that the union and the teachers had been done an injustice.”

Not long after installation, the board OK’d a collective bargaining election for Dec. 16, 1961 to decide just who would represent teachers as the sole bargaining agent.

Rejecting the advice of some who argued for the election to be held in three stages with the junior highs going first, Selden pushed a “go for broke” strategy and demanded a system-wide, “winner-take-all” showdown.

It was a big gamble. Only 13 months after the first strike in November 1960, the UFT had to convince a majority of teachers to pull its lever in the collective bargaining election. After the name-calling and worse on the picket lines, the UFT was hardly in a position to win any popularity contest, Shanker said.

“We had to win over the votes of the majority of those who crossed that picket line. We had to turn to the people who were very militant and say: ‘Even though you hate those people who crossed the picket line, even though they are scabs, make nice to them because they are the future voters,’” said Shanker.

The UFT’s tough sales job was made worse by the fact that it had virtually no budget. It was, in fact, at one point flat broke. Without an infusion of cash, the union would have no way of countering the NEA’s smear machine.

Passing the hat

To help pay the bills many dipped into their own pockets. Taking a page from the government, the UFT issued collective bargaining “bonds” to be repaid if and when the union got on its feet. They were for $100 or more, no small sum when you consider that that was more than a week’s take-home pay. Still, this was a campaign that would require more than passing the hat. To the rescue came organized labor. From the AFT came $20,000, collected from scores of small and often impoverished locals around the country. From Harry Van Arsdale and the city’s Central Labor Council came $5,000. David Dubinsky’s ILGWU chipped in another $2,000. It was also Dubinsky who made the call to George Meany that drew the AFL-CIO into the fray.

From unions around the city came experienced organizers to lend their talents to the collective bargaining drive. Among the labor loaners was a young, Harvard/Radcliffe-educated, labor economist, Lucille Swaim. A new hire in the AFL-CIO’s Industrial Union Department research division, Swaim remembers “stuffing envelopes” in the UFT’s “hole-in-the-wall” headquarters — “It was a real bootstrap operation.” But most of all she recalls being swept up in the fervor of those days. “This was no cut-and-dried organizing effort,” she said. “To the dedicated handful this was no less than the freeing of slaves. To them this wasn’t so much about collective bargaining as a revolution to free teachers who had been virtually helpless under the thumb of a martinet principal. It was very exciting.”

Whatever reservations organized labor may have had initially about teachers’ ability to organize were put aside as the labor movement threw its support behind the UFT’s collective bargaining drive. No support, however, was as critical as that of Walter Reuther, the president of United Automobile Workers (UAW).

A visionary, Reuther had long forecast that the passing of the industrial age — with its reliance on assembly-line mass production — would spell trouble for unions unless they could make headway with white-collar workers.

In teachers Reuther saw a way of establishing a beachhead among this new white-collar proletariat and the growing ranks of public sector employees.

But as a recently published biography of the labor giant makes clear, Reuther had a soft spot for teachers. Nelson Lichtenstein points out in “The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit” that it was the Detroit Federation of Teachers that had given aid and comfort to a struggling UAW in the 1930s. Even more to the heart of Reuther’s affection for teachers was that he was married to one. May Wolf Reuther was a Detroit public school teacher and an ardent teacher unionist herself.

Whatever his reasons, Reuther threw himself wholeheartedly behind the UFT. From the AFL-CIO’s Industrial Union Department, which Reuther ran, came $40,000, with another $50,000 by way of a guaranteed loan from New York’s Amalgamated Bank owned by Potfsky’s clothing workers. Said Selden, an autoworker himself in his youth, “We couldn’t have done it without Reuther.”

So it came to be that on Dec. 16, 1961, with 77 percent of all teachers casting their votes, the UFT buried the opposition, racking up 20,045 to 12,345 for both the TBO and the old Teachers Union.

Thinking back on that time, Al Shanker is quick to credit Reuther, Meany, Van Arsdale and the rest of organized labor. So too, the maniacal genius of Dave Selden. But it is the picture of “hundreds of people working: stuffing envelopes, running machines, making calls” that will forever remain with him.

P“It was a beautiful thing to see,”said Shanker. “This was a movement.”

Teaching’s no ‘bargain’ in Texas

So you’re a new or maybe not-so-new teacher. You ask yourself: What’s all the hullabaloo about collective bargaining anyway? Would my job really be all that different if collective bargaining disappeared tomorrow?

Just ask John Cole, the president of the 25,000-member, AFT-affiliated Texas Federation of Teachers. “Teachers up your way take so many things for granted,” he said. “In my part of the world, we’re still fighting for basic human dignity. I’m always telling teachers here that they don’t sign contracts but a bond of indenture.”

Hyperbole? Judge for yourself:

Texas specifically outlaws collective bargaining for teachers. In the Lone Star state, Cole said, the local school boards — there are some 1,100 scattered throughout the state — are pretty much a law unto themselves. Teachers are given individual contracts for one year that are renewed each spring at the sole discretion of the school board.

The school board is under no obligation to inform you why your contract isn’t being renewed. Said Cole: “They can fire you for good reason, bad reason or no reason at all.” Wait — it gets worse.

In Texas, a school board can unilaterally decide to reduce your salary and you’re still bound to serve out the year-long contract. Resign and you risk losing your state certification.

Contract protections? There are none. “A contract in Texas is typically one page,” Cole said. “You can be required to do anything the school district tells you to do at whatever salary they say.” He pointed to a recent case in which a teacher protested having to collect football tickets for an after-school game. Lost cause.

Cole cited another case of a teacher who had been evaluated as excellent in her subject matter. Exemplary or not, a new principal had someone else in mind for her job, so she was assigned to teach Spanish — a language of which the teacher spoke nary a word. Well, after a few months the teacher was observed and — surprise — her performance wasn’t up to standard. She was terminated. The Texas Federation of Teachers lost her case, too. Said Cole: “In Texas, you will teach what they tell you.”

As for salaries, Texas is near the bottom. The $19,500 starting pay isn’t so much the problem; it’s a top salary of $35,500 that discourages teachers from making the classroom a career. “The districts like turnover — it’s a cost-saver,” Cole explained. Besides, he said, as far as the school boards are concerned, “experienced teachers frequently are trouble.”

Then again, Texas teachers aren’t entitled to Social Security coverage and face their retirement years with no Medicare. As for pensions, teachers underwrite a substantial portion of their pensions with the school districts contributing nada.

So, such conditions must make it pretty easy to organize a union, right?

This is Texas, son.

“When new teachers ask me: ‘If I join the union, could I get fired?’ I always say: ‘Yes.’

Originally published in New York Teacher, September 16th, 1996